“If technological memory produces collective memory, and is not satisfied with reproducing it, the distinction between artificial and natural, technological and psychological, becomes increasingly tenuous and subject to caution. Such technologies are not only technics of conservation and transmission, but also techniques for the impression of memory (here in the “psychological” sense of the term). ICT troubles the most assured oppositions, notably on the level of “software” narratives that the media articulate: on a daily basis, the media narrate life in anticipation, with such a force that the narrative of life seems ineluctably to precede life itself. Public life is produced en masse by these programs; all sorts of interfaces introduce themselves into the intimacy of each and every life in such a way that the distinction between public and private becomes problematic. . . . The automatisation of the process of memory production, as quasi-prosthetic autoproduction, comes to impress individual memories beyond national, ethnic, familial, and ethical frontiers and barriers. This can inspire the image of a “re-alisation of absolute knowledge,” which would also be the absolute “derealisation” of knowledge, and can provoke massive anxiety. “

— Bernard Stiegler in ‘Technologies de la mémoire et de l’imagination’ in Réseaux vol. 4, no. 16 (1986): 61-87

In this essay, I offer an outline of the problem of the absence of art, science and technology collaborations in the domain of International Relations. This narrative engages with three key individuals who have shaped and are part of the history of art, science and technology collaboration in Canada and internationally— Sara Diamond, Jean Gagnon and Nina Czegledy—and reflects on the state of the field and the prospects of situating it in the domain of International Relations.

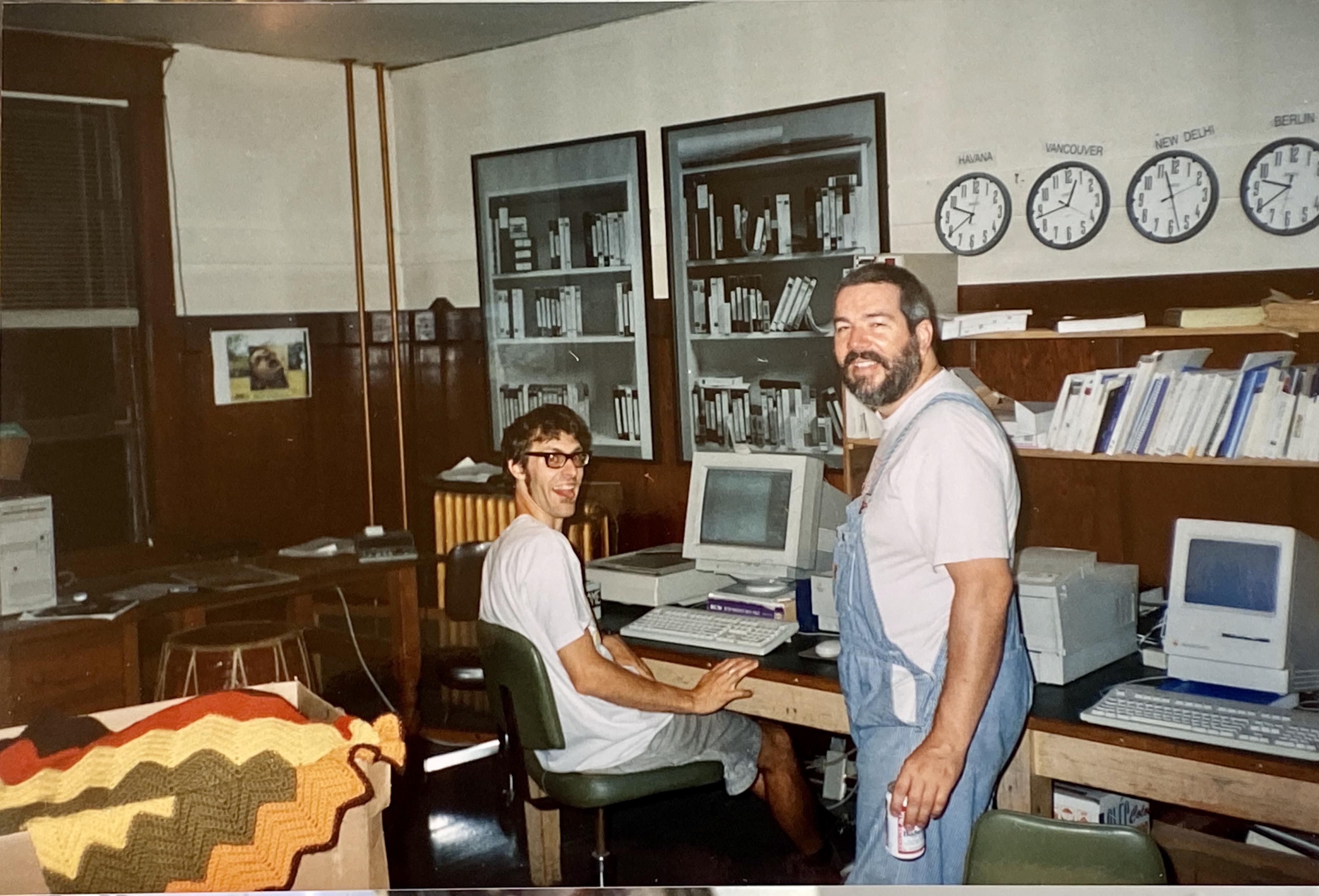

Vancouver’s media arts ecology was unique and I remember visiting the Western Front (WF) to take workshops with Bob Richardson, also known as Spencer Cathey, on computational/integrated media. Bob was one of the many U.S. draft dodgers who had become part of the Vancouver art scene and a geek who made computer programming and its possibilities in the art ecosystem a distinct experience with his expertise in image processing. He was influential in pioneering research into a new medium, “Digital Image/ing.” In 1985, Bob gave his now famous lectures on Computer Graphics Survey – a series on state-of-the-art form and some mathematical principles underlying computer graphics.

The Vancouver media arts scene was “hyper active media art scene— a hotbed of experimentation, collaboration, technical play and radical engagement, with a proliferation of organizations engaged with media art”[1]. While in Vancouver, in the 1970s the world of communication technology was being transformed by the advent of McLuhanism, the critique of mass media from the Frankfurt School, the severe contestations on the MacBride Commission on the New World Information and Communication Order, and the search for Third Cinema. Culture was called into question as much as its history.

The opening quote of Bernard Stiegler comes from the english translation[2] of his first published philosophical work articulating the challenges of thinking about technology and its relationship with culture, nation-state and the making of history. This text offers a philosophical impetus as well as a context to the contestations that were happening in the post-Bandung Afro-Asian solidarity against the dominant Cold war paradigm. A mainstay of the decolonization after the post world war II phase, this Afro-Asian solidarity made a call for a New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO). The debates began in the 1970s and lasted till the end of the Cold War. These debates were encapsulated under the rubric of the MacBride Commission, a research commission hosted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization and was named after its chairperson, Sean MacBride the Irish diplomat and founder of Amnesty International.

The MacBride Commission in its final report titled Many Voices, One World summarized the multitude of research papers that underwrote the call for a new world order. The fate of the report and unprecedented opposition by the Western powers especially the United States demonstrated how hard it is to give “others” voice.[3] One of the impacts of this heavy handedness in crushing even the voicing of an alternative and differently imagined world and its history discouraged further struggles around these issues at the United Nations.

“ The MacBride Commission in its final report titled Many Voices, One World summarized the multitude of research papers that underwrote the call for a new world order.

Narendra Pachkhede[4], makes a pertinent observation about this period of contestation pointing to the engagement of Non-Aligned Movement of the Afro-Asian solidarity had an interesting history to the interaction of art, science, and technology in the countries aligned to the movement. Discussing an unpublished report he authored, “Experiments in Writing History: Of Poiesis, Praxis and Media Art”. He says: “In the Non-Aligned World the interactions and collaborations between artists, scientists, anthropologists, engineers and technologists from the Non-Aligned Nations and the US had surprising and distinct outcomes. For instance, the interactions at Zagreb, in the former Yugoslavia, led to the birth of a new aesthetics—New Tendencies[5], while in India it led to the birth of Indian Television.”

In this connection, it is worth mentioning the significant fact that, for all the differences between the factors involved, 1961 was not only the date of the first New Tendencies exhibition, but it was also the year in which Belgrade hosted the First Conference of the Non-Aligned Countries, with the attendee of several Heads of State. Exhibitions like New Tendencies —only non-aligned Yugoslavia had the capability to host anything of the kind. New Tendencies developed into an international movement and network of artists, gallery owners, art critics, art historians, and theoreticians, transgressing the Cold war barriers and exhibiting both artist from both sides, the proverbial East and West. They presented instruction-based, algorithmic, and generative art. In an essay introducing the show: Histories of the Post Digital: 1960 and 1970s Media Art Snapshots organized in Istanbul in 2014-2015, Darko Fritz writes, “following the rationalization of art production and the conception of art as research that was theoretically framed by Matko Meštrović, Giulio Carlo Argan, Frank Popper, and Umberto Eco, among others, New Tendencies was open to new fusions of art and science. Light and movement were the new materials, shaping art styles as luminokinetic art. Participation with artworks was understood to be an examination of democratic political praxis, and visual research was seen as a way of learning it.”[6] In such a world making, in delineating the geographies of Media Art history, this called into question the simplified categories — national or regional— that homogenized art history. For instance, no longer one could speak of one European Media Art History. “New Alliances, some of them with China, Latin America or the Arab World, built unexpected bridges. The ideological war shifted from Europe to the Third World, to cultural contexts where “modern states” still had to be created.”[7]

“Before the fall of the wall, there was a deep history of visual artists collaborating with scientists in Hungary and other countries in Eastern Europe, to explore physics, geometry, and abstraction. Brazil saw a fluorescence of SciArt and Art and Technology through the 1960s, with deep influences from European refugee Vilém Flusser, echoes Sara Diamond[8].

“When we founded the Centre for Research and Documentation (CRD) at the Daniel Langois Foundation (DLF), when we created the program of Researcher in Residence, one of the aims was to start documenting and interpreting such histories. Now we did not limit these research to Canada only, but rather as somewhat North-American. Nothing happens in isolation. Therefore we acquire the Vasulka archives as well as the A/V archives of 9 Evenings of Theatre of Engineering and others, people and organizations that had an impact in Canada,” says Jean Gagnon[9].

Gagnon continues, “The fact that American archives ended-up in Montreal is a testimony to the fact that at the beginning of the 21st Century, there was very little interest in these even in the US. So the DLF played a great role in defining a field of research based on archives. And through the researcher in residence, we were able to promote important research and publications. Those researchers came from different places and they range from old-timers and important scholars like Gerald O'Gready, to young French scholar such as Clarisse Bardiot or Canadian then Ph.D. candidate Caroline Seck Langill. We also helped Ricardo Dal Farra, an Argentinian now Canadian, gather and publish a Latin-American database of pioneers in electroacoustic music and write a history of contributions of the continent to that field. All this to say, that our focus not being always Canadian, we favoured important research that gave examples of what could be done or needed to be done. It certainly placed Montreal and Canada at the forefront of this young field of media art histories, that has been taken on by others now. One of the aims was to start documenting and interpreting such histories. Now we did not limit these research to Canada only, but rather as somewhat North-American. Nothing happens in isolation.”

“Canada is not the only outlier when it comes to American or European historiography. Mexico has been a fantastic epicentre for new media art, virtual reality, interactive performance,[10] as has Brazil, and more recently Colombia. India has been home to important practitioners and intervenors, as has Senegal”[11], quips Sara.

This made me ask the question as to how are these itinerant histories accounted for in the study of International Relations? More specifically, where do art, science, technology figure in the discipline of International Relations, and in its practices manifesting in the domains such as foreign policy, cultural diplomacy, and cultural trade?

“ …where do art, science, technology figure in the discipline of International Relations, and in its practices manifesting in the domains such as foreign policy, cultural diplomacy, and cultural trade?

In the 21st century, the study of International Relations has been impacted by multiple intellectual interventions as they intersect in defining the contestation of the State-centric dominant anchoring of the discipline and its practice. The current paradigm of neoliberal and neo-realist schools of thoughts have focussed on the centrality of the nation-state in defining the international order which is articulated in terms of war and peace.

Given the urgencies of understanding today’s global politics of culture, the irony has not escaped one’s eyes in the failure of International Relations to integrate contemporary conceptions of art and culture and its histories.

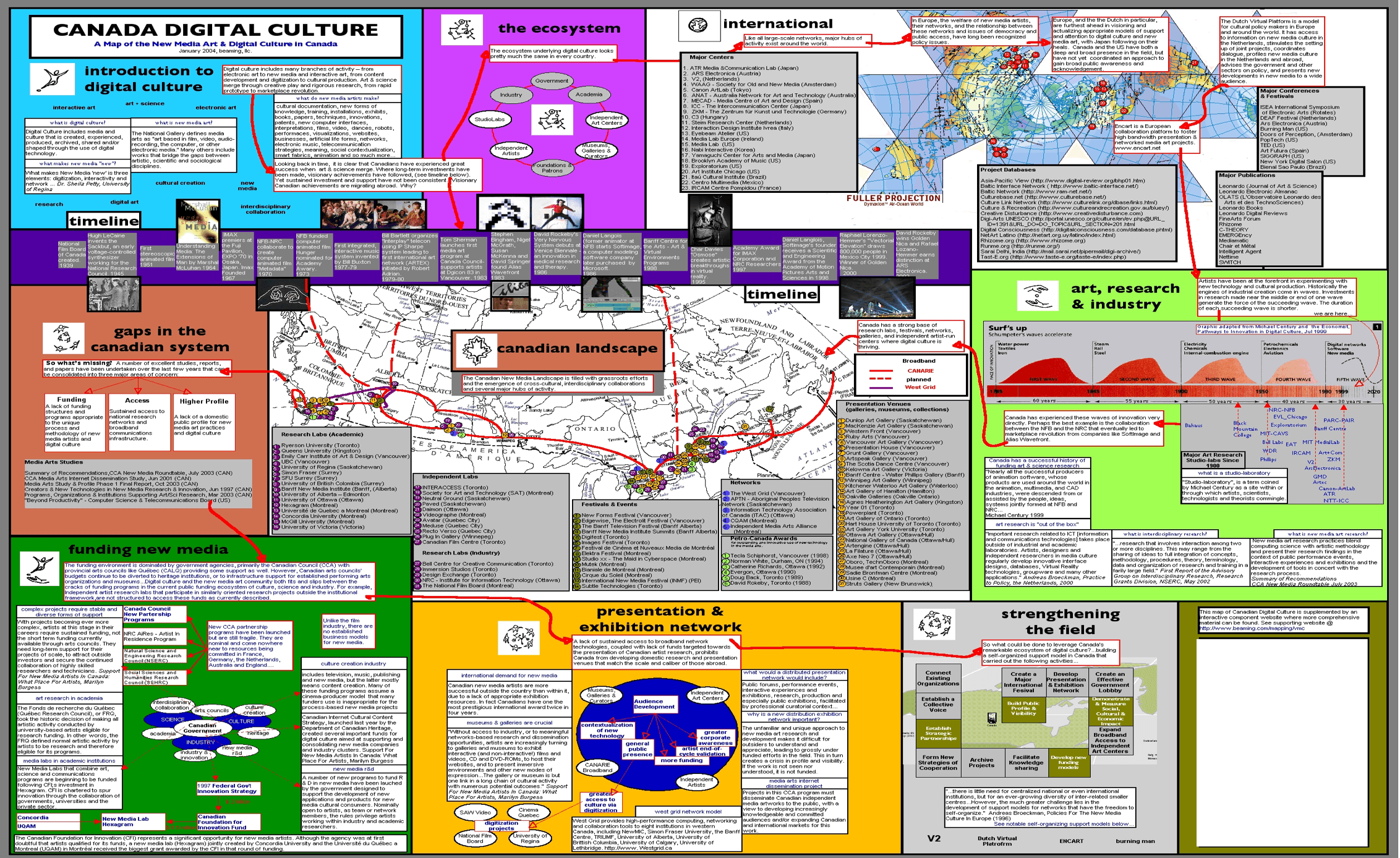

Sara Diamond points to an important aspect of how policy making became a drawback in this light. She says “perhaps more telling is that Canada separated what had been a combined ministry of Communication and Industry into two silos, one dealing with “content” and the regulation of content and its funding, and the other with the emergence of technology, including in the telecommunication and IT sectors. This was a mistake which resulted in a far more conservative approach to potential combined creative/technology inventions, solidified experimentation in terms of scale up funding on the periphery, placed design into purgatory, leaving Canada as one of the only advanced capitalist countries without design policy or strategy.”[12]

Marked as the year of the pandemic, the decade ending year of 2020 retain its salience as the bookend of three decades since the end of Cold War. It has become a significant marker for the critical decades of the postwar period as it marks an eventuality which further set in motion a series of events followed by historical processes which have found a resonance in the current state of the world. Art and Culture has been central to it, yet, not central enough for the study of international relations. The post-war period offered the rhetoric of Cultural Diplomacy which transitioned into the ideas of Soft Power, and both these modalities remained status quoist to retain the centrality of the nation-state in defining security and in the making of the world order.

European networks have become critical of such dominating approaches of defining world order. Similarly, there is a challenge to contemporary study of international relations study in the emergence of a new cohort in International Studies Association in the USA which focuses on Science, Technology, Art in International Relations (STAIR)[13] much like the “art and politics” group in the British International Studies Association (BISA). In Canada, the study of International Relations and Foreign Policy studies have ignored the role of art, artists, artist networks and cultural institutions. Though, the rhetoric of Cultural Diplomacy is on the rise again, it is embedded in the Cold War framework. The Queens University affiliated, the North American Cultural Diplomacy Initiative (NACDI) is a recent example of University based research program in this area.

Despite the growing insertion of cultural identity and art as an issue-areas in the study of international relations, art institutions exhibition making, art movements, artists networks, art events and festivals are some of the most understudied areas in the study of international relations. But with the rise of constructivism[14] in international relation there is a new found appetite for bringing into its fold these very actors and their agencies that enables to open up new areas of study as well as foster the strengthening of a discipline in 21st century.

Much of the current literature in the affiliated area demonstrates the use of art history on the axis of London-Paris-New York while discussing role of culture in international relations. Dismantling this bias is imperative and this essay calls to addresses this specific gap by foregrounding Canadian Media Art history, exhibition making, art events, art practices and their significance to the study of international relations.

Jean Gagnon points out: “this is true, but Canada is not unique in this situation. It is the case for most peripheral countries. If you think of Argentina, which pioneered a lot of art and technology endeavours in music and in visual arts, it is also rather absent of the international landscape. Although some efforts have been made here and there, by Leonardo/ISAST for instance, much remains to be done. For instance, I am still waiting for Michael Century to complete and publish his book on the role of Canada in pioneering art and computer experiments. It is true that if you do your research, you will find quite a lot of information dispersed in diverse publications, anthologies, catalogs, articles, and so on. But these are difficult to gather and we are still waiting for a monographic essay on that history. As often, Canadians are not very good at promoting their history which is often quite remarkable and unique. I guess also, the younger generation right now is more concerned with other pressing issues such as redefining identities, systemic discriminations, and so on, than looking back at recent achievements that may not speak their language.”[15]

As an illustrative example, I am going to refer to one of the more recent literature survey on art, science and technology by the Swedish Art historian, Anna Orrghen.[16]Orrghen offers three thematic traditions: pioneer stories, writing aiming at mapping and categorizing, as well as those problematizing and contextualizing the filed. In this endeavour she takes Frank Popper’s term “technoscience art” which he introduces in the 1987 issue of Leonardo.

Responding to Popper’s term of “technoscience art” and its subsequent framing of art-science-technology collaborations, Sara Diamond responds to such framing to suggest that “Popper drew an important line in the sand in terms of identifying a specific set of practices that he argued needed to be recognized in the 1980s. He cites historical precedents (E.A.T. for example) as well as a threshold and convergence of emerging technologies. Popper, in his statement following the Venice Biennial focused on Computers, Telecommunications and Audiovisuals. These categories represented significant practices yet don’t adequately validate practices that were already underway in the 1960s which were focused on environmental arts and sciences, and BioArt which could include early feminist interventions around the body, as well as ways that artists and scientists were collaborating outside of the emerging digital space. The early thinking in art and technology to some extent avoided theoretical frameworks that critiqued technology, such as the Frankfurt School, or drew from emerging feminist or post-colonial theory. Yet other artists who were engaged with art, engineering, technology, and science, were working in these critically informed ways by the 1980s. I realize that I started in 1992, a half a decade later, but the work that I undertook at The Banff Centre and the Banff New Media Institute tried to build a wider, more global, and disciplinary inclusive base and sets of theories, for notions of “new media”.[17]

“On another note, a fundamental point that Popper makes is the need to “maintain a distinction between artistic imagination, scientific investigation and technological experimentation. I am not in complete agreement with these distinctions as they come from a division of labour that is reified in Western practices but less so in other Art/Sci histories and in the holistic relationship between arts, culture and invention in Indigenous cultures. Dr. Michael Century was at The Banff Centre before me and initiated the Art and Virtual Environments activities, developed a concept of studio laboratories that brought together creative arts’ methodologies and technological research in an experimental and at times instrumental context. His work shows the ways that these separations can become false. Artists like David Rokeby or designer Bill Buxton are inventors as much as creators. My own project CodeZebraOS led me to working intensively in data visualization in creative and instrumental ways.”[18]

Current Canadian activities are exemplified by (for example) the Montreal based Hexagram international network dedicated to research creation in the fields of media arts, design, technology and culture. Gagnon says, “I was among the founder of Hexagram in Montreal. The DLF was its first source of funding. I also gathered a group of private investors (including the Cirque du Soleil) to create a fund that lasted a few years and was devoted to financing endeavors involving art and new technologies. I have been Hexagram's Vice-President for seven years and as such, I helped to define its first directions and programs. Although the evolution of Hexagram has been hectic at times, it was the first attempt, I think in Canada, of such an institute that put art and artists at the center of technology (and scientific) research within a university consortium (Concordia and UQAM). I'm not sure it always succeeds in delivering what it promised (knowledge transfers to industry and sustainable art, science, technology projects) but it attempted what had never been tried to such a degree, which is to have artist-driven technoscience research.”

“ …Current Canadian activities are exemplified by (for example) the Montreal based Hexagram international network dedicated to research creation in the fields of media arts, design, technology and culture.

Despite such active scene one observes a plateau in these areas of collaborations and research. Often addressing the political expediency, and invoking an unimaginative innovation program, it is no wonder that despite such active scene one observes hitting a plateau in these areas of collaborations and research. Gagnon concurs, “I guess today, I am very much careful with my enthusiasm relative to all that field of endeavors. I don't think it has delivered much apart from allowing funding to be derived towards art and technology research in University settings, which was necessary at the time and means that Canada remains an important country in the field.”[19]

Talking to Nina Czegledy, a longtime Board member and former chair of International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), which was initiated in 1988, she says,“an obvious change is observable in the perception of Art, Science and Technology in Canada and abroad. Multi-disciplinary academic courses, dual degrees, artist residencies, exhibitions and conferences are offered today which were not available three decades ago. As an ISEA board member from 1995 and Chair from 2000 to 2008 and active participant in ISEA Symposia to this day I was privileged to witness the global growth of art, science and technology visibility around the world. More promotion and financial support is needed to make all of the above publicly visible in Canada and especially Canadian art abroad. When I started touring Canadian trans-disciplinary art abroad (often in distant countries and continents) support was available from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Department of External Affairs including the Canadian Embassies. My projects were not spectacular, rather work by Canadian Women Artists, Indigenous artists etc., but they were very well received from New Zealand to Russia — everywhere abroad.”[20]

Responding to the question of the relationship between Nation-state, Culture and Technology, Jean Gagnon has a more direct response: “The Canadian government under both Harper and Trudeau has been quite lame relative to issues of technology and culture. Again, cultural domination from not only the US but now China continues, leaving peripheral countries with few chances of reaching the public even on a national level. Sometimes, I would like to think that the Francophone culture of Canada has more hope not to be dominated by foreign cultures, but in reality, it might be an illusion.”[21]

Through my conversations in writing this text, I see the imperative of defining a clear agenda—to situate the arts, science and technology collaborations and its histories firmly within the study of International Relations— and delineate its prospects. Towards this an inquiry into the capacity of Canada’s self understanding and articulating its policy positions in clearer terms premised on a engaged reading of its history, in particular its Media Arts history, to realize the potential of breaking free of the legacy of Massey Report[22] while engaging with the rich practice of collaboration between artists, scientist and technologists. Given such prospectus and aided by the impetus on Digital, and in name of innovation, the quote at the beginning of the text becomes all the more poignant and bear a potent valency.

Sarah Cook and Sara Diamond edited Euphoria & Dystopia: The Banff New Media Institute Dialogues, Published by Banff Centre Press, Riverside Architectural Press, 2011

Anna Orrghen (2017): Surveying the literature on technoscience art: from pioneer stories to collaborations between artists, scientists and engineers as the object of study, Digital Creativity, DOI: 10.1080/14626268.2017.1322986

P. Singh , Madeline Carr, Renée Marlin-Bennett Edited Science, Technology, and Art in International Relations, New York and London: Routledge, 2019

Bazin, Jérôme, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, and Piotr Piotrowski. "Introduction: Geography of Internationalism." In Art beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945-1989), edited by Bazin Jérôme, Glatigny Pascal Dubourg, and Piotrowski Piotr, 1-28. Budapest; New York: Central European University Press, 2016. Accessed September 20, 2020. doi:10.7829/j.ctt19z397k.5.

Bernard Stiegler, Technologies of memory and imagination, translated by Ashley Woodward and Amélie Berger Soraruf in Parrhesia 29-2018: 25-76

DeeDee Halleck, Hand-Held Visions: The Impossible Possibilities of Community Media, published by Fordham University Press, January 2002

Margit Rosen edited, A Little-Known Story about a Movement, a Magazine, the Computer’s Arrival in Art: New Tendencies and Bit International, 1961–1973, MIT Press, 2011

Armin Medosch, New Tendencies: Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961–1978) MIT Press, 2016

William Preston, Edward Herman, Herbert Schiller, Hope and Folly:The United States and UNESCO Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989

MacBride Commission. (1980) 1984. Many Voices, One World: Towards a New, More Just, and More Efficient World Information and Communication Order. Report of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems. Abridged ed. London: UNESCO.

Before GIFs and net art, there was Telidon. Telidon was a protocol invented in Canada in the late 1970s that let people dial in to central servers over the phone lines to view computer graphics on their TV sets. Telidon was mainly meant for online shopping and banking, but it wasn’t all business. Artists in Toronto obtained one of the desk-sized computers used to create Telidon graphics and formed a thriving community around it before Telidon disappeared in the mid 80s.