Dear Mr. Turing,

It was Ian McEwan’s novel, Machines Like Me, an alternative historical narrative set in the 1980s in which you appear as a character and have, crucially to the plot of the text, developed twenty-five robotic humans named Adam or Eve, that prompted this letter. Yes, you’re literally dead, and have been since 1954 when cyanide killed you, but you’re literally alive in the novel, a well-rounded but stern character, and it is this dynamic, and that writer’s excellent characterisation of you, that has clarified an idea that has bothered me for years though I may never articulate it. What if a character, like you in this novel or in any fictional form, are the closest we’ll ever get to artificial intelligence? What if people aren’t like machines, but literary characters — which are constructions machined through the artful technology of language — are like people. The question of artificial intelligence, then, might be more a matter of how we structure the simile, or which is the subject and which is the object of the sentence. Let me explain.

I first read your seminal essay on AI years ago, long before Benedict Cumberbatch played you in that movie about the codebreakers decrypting German communications during the Second World War. When I was in university studying literature and linguistics, I had a friend, Beach, a computer science prodigy, who told me about you, and about people like Gödel and Frege and other writers on the far side of that wall separating the liberal arts from science and technology. He regularly poked fun at what I was learning, said it was basic training for a few years of charming conversations but irrelevant to the future of civilization. He was surprised that English majors like me weren’t getting computer literate or even reading texts in the nascent field of AI, so much of which, he never tired of reminding me, dovetailed with issues of language and representation. What I was studying, whether Milton, Blake, or Foucault, was educational masochism. What’s the use knowing that words scaffold all human thinking and enterprise, Beach would say, when the future will require technical know-how that just gets things done? What business did I have playing at bohemian intellectual, with my Norton Anthology, Derrida books, and a band of misunderstood artsy friends, while he was reading Panini and Chomsky and working on a robotic glove that renders hand gestures into speech via some complex neural networking that required studying math not metaphor?

I’ve lost touch with my friend, but I know he’s a big-name researcher at a world-class institute, while I happily teach stories and poems, maybe the occasional sentence parsing diagram, to semi-literate college students itching to get their dreaded English requirements so they can get into stem programs over at his university. I know the paradigm has tilted in the world in Beach’s favour. We live in what Kenneth Burke, a rhetorician who’s no longer widely read, called a “technological empire” that established “the conditions of world order.” I also know that, though English majors now have something called “digital humanities,” people in the humanities still have to get with the program — read your essay, for starters, and learn the grammars of computer coding and the mathematical languages at the centre of the digitized world. But I also know, and I’d like to think you’d agree but I’m not sure if you would, that it’s more important than ever to defend literacy in the humanities in its most traditional mode, with the ideal of teaching people how to respond to what is most creative in their culture by teaching critical reading practices, specifically the rhetorical wherewithal to make sense of the mystifying language that frames much of understanding of technologies like AI.

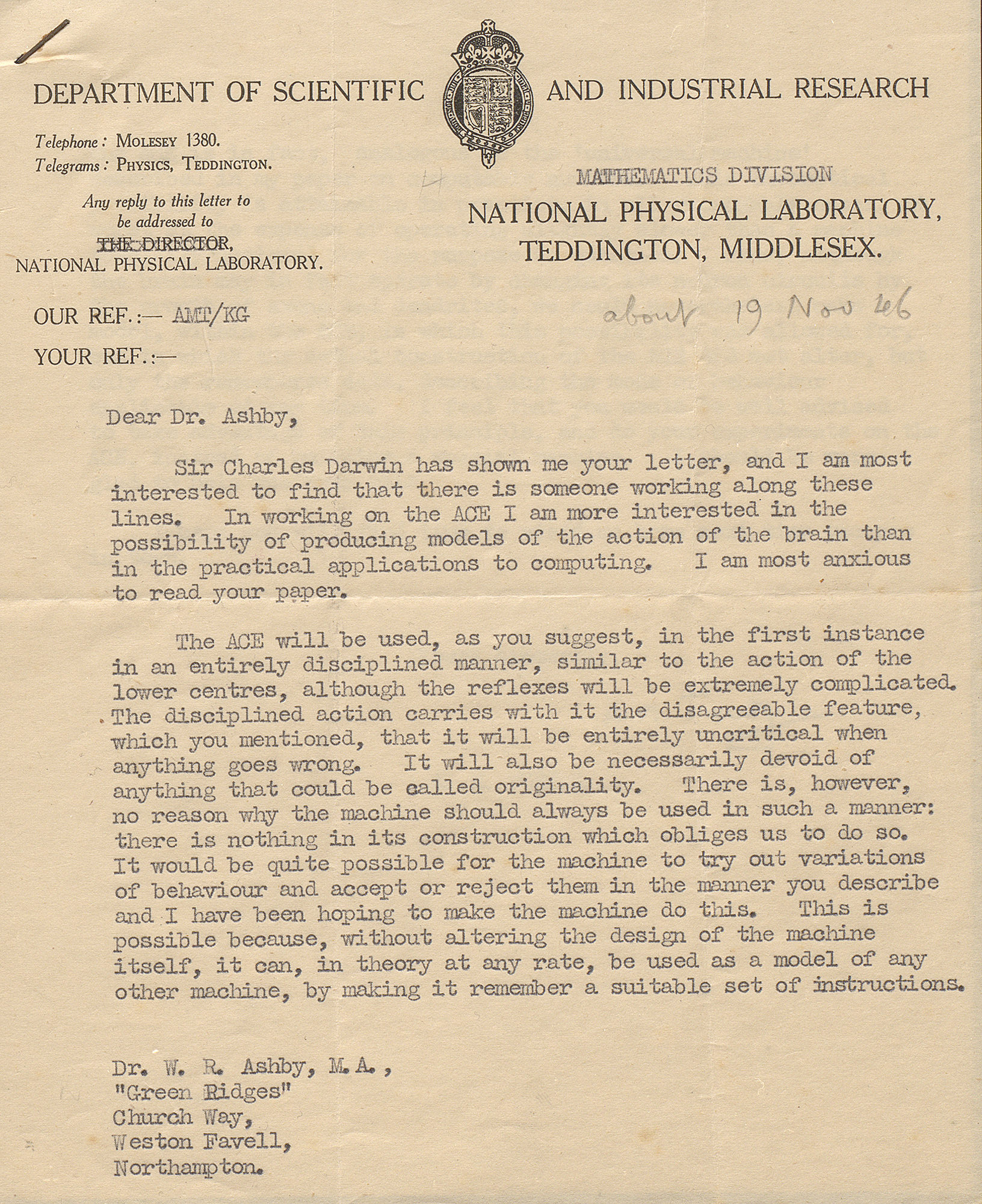

Which brings me to your essay, which I respect mostly for its acute focus on words. You start with a question, “Can machines think?” but instead of answering it you deconstruct the meanings of “machine” and “think.” People don’t think enough about their words, especially in the sciences, where they seem to believe in a purified, literal language, diametrically opposed to poetry and fiction, where each word equals a thought or thing in the real world. I can’t imagine that you believe that metaphysical pretense! I also like how you ease into your argument by sketching out the scenario with the three rooms connected by screens. A woman and man in two of them and a judge in the third who decides, based only on the textual evidence communicated to him via typed language on a screen by the other two, which of them is male. In what I’ve come to think was a sly nod to the cybertransexualism of the future — was it? — you charge the man and woman with the task of convincing the judge they’re female. Fascinating, and not only because there are identifiable differences in how we speak and write. But then you replace one of the first two with a computer and the judge has to decide which of them is human. This “imitation game” — the notorious and notoriously misunderstood “Turing test” — is quite the thought experiment. If the judge is as likely to pick the human as the computer, then the machine, you conclude, is a passable simulation of a human being and, consequently, intelligent. That’s where your language game opened a Pandora’s box of scientific wonderings and so many speculative allusions in pop culture — Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, Terminator, Her, the works of Asimov, Dick, Gibson, Kurzweil — where, so the typical narrative goes, AI and humanity square off.

Your essay, to my simple English prof mind, is quite the exercise in argumentative finesse. The way you list claims against your pro-AI position only to knock them down, logically with an eye to their contradictions and linguistic shenanigans. I have to say, though, that I’ve taught “Computer Machinery” a few times and, although students seem excited when I tell them they’ll be reading an essay by the godfather of all computer science — likely because they think they’ll be getting something like the online lifeworld of social media and video games they’ve inhabited most of their lives — most don’t “like” it, certainly not in the Facebook way. They don’t want to read the theological, philosophical, and rhetorical position you entertain and refute. To them, sadly, digital literacy is much more aligned with the names of the well-branded corporate figureheads of AI, like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, not the name of the brain behind their profitable operations.

In any case, when my university pal used to say, echoing you, that “machines can think,” I couldn’t wrap my mind around it. Nor with your claim, which I’m sure he also believed, that “at the end of the century the use of words … will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.” Sorry, Mr. Turing. I can’t imagine a time when words will be that perfect. My mind is insufficiently equipped to comprehend the narrative implied in that technological idyll. Maybe you believe that language can reach that pristine Adamic state? Or maybe you attach different meanings to the phrase “can think?” Sure, I have a relationship with my iPhone built on a kind of psychotic personification, but that’s not because it “can think,” but because I’m not thinking. Yes, I was as engrossed as the next guy a few years back when the chatbot posing as a thirteen-year-old Ukrainian boy tricked judges into thinking it was a human, though I suspect “Eugene Goostman” passed the Turing test because it was characterized — or is it programmed? — with empathy-inducing traits, like bad grammar and a propensity for juvenile expressions. It’s one thing to think, like you do, there are “imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game.” I agree! But this might be a simple matter of programming a computer with a skill set to “read” inputted text — say, a Hemingway story — quantify and differentiate its complex and simple sentences and produce a nice data visualization showing who uses which. Or outfitting one with gps and audio recognition software capable of distinguishing interrogative syntax so it can respond to questions like “Siri, how far is Bletchley?” There have been cataclysmic shifts in technology, so many that Silicon Valley types call it “fintech,” the complete collusion of finance capitalism with technology, but the celebration of AI on the grounds that a machine “can think” seems hasty to me, a premature panegyric when there’s a chance it should be a dirge.

I have to say, Mr. Turing, that the language of AI is marked by a remarkable degree of hyperbole and figurative ostentation given that by most accounts science and technology pride themselves on the dream of an objective language where words are sutured to things with mathematical precision so much so that we never need to pay attention to them. An irony, wouldn’t you say, given the punctiliousness of your essay?

“ People don’t think enough about their words, especially in the sciences.

Earlier this year, the World Economic Forum made AI a signature theme at their annual Davos affair. In collaboration with “key stakeholders” from one hundred companies, the WEF put together a nine-page text called the Empowering AI Toolkit, a document aimed at educating board members of companies about AI, which is “already altering the way people live, work and receive care,” though none of it addressed the “people,” their lives or jobs, in that comprehensive clause. Clicking through the WEF’s pleasing online resources, I found this little bit of rhetorical mania from Alphabet Inc.: “AI is one of the most profound things we’re working on as humanity. It’s more profound than fire or electricity.” Metaphorical flamboyance is good marketing, and corporate types aren’t in the business of thinking of “AI” as anything but another form of profit maximization, but the comparison to “fire” and “electricity” — to say nothing of the personification of “humanity” — gob smacks me as mere puffery coming from the CEO of Google’s parent company. Further along my search of what people are saying about AI, I read about cifar, the homophonic acronym for what used to be called the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Institute, which happens to be sponsoring a course in something called “dlrl.” Sinister organizations, as someone said, lurk behind the mask of acronyms, and this infernal shorthand signifies “deep learning” and “reinforcement learning.” Irrespective of those heavy adjectives, neither “learning,” is pedagogical in any but the most managerial sense of the word, both are attached to that umbrella term “machine learning” — a vital personification in AI, as you know — and are framed by cifar as pedagogies that, well, see far into the future. Facebook’s omniscient point man, I learned further along, opts for more mundane hyperbole, saying one day a couple years ago during a live feed when he fielded user questions about AI while barbecuing in his Palo Alto backyard. “I am optimistic,” Zuckerberg said. “I think you can build things and the world gets better. But with AI especially, I am really optimistic,” though later that same year his company shut down two AI bots programmed to communicate with each other in English because they started conversing in gibberish. I also came across these sentences at deeplearning. AI: “Deep Learning is a superpower. With it you can make a computer see, synthesize novel art, translate languages, render a medical diagnosis, or build pieces of a car that can drive itself. If that isn’t a superpower, I don’t know what is.” So says the CEO of the corporate and educational venture, Andrew Ng, who also happens to be cofounder of Google Brain, that megacorp’s AI research team. Over at Accenture, one of the companies that worked on that Toolkit for the WEF, I read that people are so used to technology today that they are “post-digital,” which I didn’t quite understand: “People don’t oppose technology; they remain excited and intrigued by it.” I also read Accenture’s Managing Director of AI, and co-host of their AI Effect podcast, Jodie Wallis, ask Prime Minister Trudeau “how to get all Canadians excited about AI.” To which he replied “this transformative technology” is strong “because we’re surrounded by so many strong AI ecosystems in Canada.” Metaphors conflating culture with natural phenomenon, like an “ecosystem,” require close reading with an eye trained on ideological obfuscation, though frankly all of the AI hyperbole I came across sounded so good and brimming with metaphysical bubbliness that it wasn’t meant to be “read” as much as skimmed and accepted. I’m not sure why it troubles me so much, but all this sweetness and light signifies nothing but the essentially capitalist nature of AI. Enthralled by the novelty of tech, the general public forgets the profit motive at its core. That forgetfulness was perhaps best articulated by Rachael, if you recall the Nexus-7 replicant in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, who levels Deckard with this AI poetry: “I’m not in the business. I am the business.”

Aristotle said hyperbole is common among “young men” and “angry people,” which probably isn’t news to anyone who’s experienced either, though I’m curious to know what you make of the blustery bs in AI talk. At one point in your essay, you write that instead of having an intelligent machine simulate an “adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child’s?” Then, literally following that old tabula rasa metaphor that organizes your point, and so much Enlightenment thinking, you say “the child brain is something like a notebook as one buys it from the stationer’s. Rather little mechanism, and lots of blank sheets. (Mechanism and writing are from our point of view almost synonymous.)” How captivating that you connect writing here with mechanism; no doubt, it’s one of our first technologies, as Plato knew when he wrote about Thoth, the old Egyptian god of writing who offered King Thamus writing as a “remedy” to help human memory, only to have the king refuse the technology on the grounds that it will make people forgetful. Presumably, if your computer machinery’s pages were written on, this writing would be literal language, not pernicious and misleading metaphors. Or would it?

While searching for what people were saying about AI, I found that the word “literacy” is used liberally, perhaps even gratuitously, a sort of public service euphemism signifying an unbearably meaningless benchmark. An article published as part of that WEF Davos forum named “digital literacy” the first “tech skill” that will be part of every job in the future, and I’m sure they’re right, though their definition of “literacy” seems closer to vocational competence rather than “reading” in any sense of the word I spend my days teaching students. An OECD publication, The Future We Want, on the question of technology and “education change,” announced that schools should prepare students “for jobs that have not yet been created, for technologies that have not yet been invented, to solve problems that have not yet been anticipated.” There are some pretty words about students needing to “exercise agency, in their own education and throughout their life,” but then the document lists two specific requirements: a “personalized learning environment,” which sounds ambient enough though I’ve no idea what it means, and “literacy and numeracy”: “In the era of digital transformation and with the advent of big data, digital literacy and data literacy are becoming increasingly essential, as are physical health and mental well-being.” The remarkable point in this baroque cluster of language, is that clause about “health” and “well-being,” which I suppose might indicate that, for all its sublime goodness, the digital world might lead to an array of illness. AI, the OECD continues poetically, “is raising the fundamental questions about what it is to be human. It is time to create new economic, social and institutional models that pursue better lives for all.” A pretty thought, though I wonder how these models relate to “literacy,” and whether they don’t just mean students should be vocationally trained to work with AI to fit into the technocratic system rather than taught to critically read the language and literature that holds that system in place, or at least be “literate” enough to enact their “agency.” Should I have read “literacy” metaphorically, do you think, and if so what does the metaphor signify, exactly?

There is a climactic moment in McEwan’s novel when, through the mechanism of his narrator’s words, you, Mr. Turing, are explaining the development of AI’s to Charlie, the lead character whose Adam has, along with most of the twenty-four other Adams and Eves much to your chagrin, broken the rules. There is one form of intelligence, you say, that all Adams and Eves “know is superior to theirs”: the child’s mind “before it’s tasked with facts and practicalities and goals,” you tell him, and then specify that the factor differentiating artificial from human intelligence is “the idea of play — the child’s vital mode of exploration.” This occurs in a much longer discourse at your fictional house, where you have been expostulating, with a degree of clarity perhaps only poetically licensed to a literary character, on the various differences between human and artificial intellects. It’s not that you contradict the argument in your essay; not exactly, but you do feel free to ad lib and riff on your argument outside the constraints of academic prose. In “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” you say “I do not wish to give the impression that I think there is no mystery about consciousness,” yet apart from following up by saying that this mystery needs to be “solved,” which I suspect means explained away by scientific reasoning, you don’t address the matter. McEwan’s extrapolated you, by contrast, lingers on the subject when speaking to Charlie, touching on, for example, the messiness of contradictions that define us reasonable creatures with a propensity for unreason — “we love living things but we permit mass extinction,” to name just one — but never forces a resolution. The fictional you is as intent as the you I read in your essay on creating an artificial intelligence capable of passing the Turing test but this intelligence must inhabit contradictions instead of setting out to “solve” them. Periodically, I think I understand what you mean.

You say, not in your essay but in your role as a character, that the ultimate hurdle that people need to overcome is a matter of how you structure the simile. The machine is not like a game of chess, a “closed system” which “is not a representation of life.” The machine needs to imitate an “open system,” which is “full of tricks and feints and ambiguities and false friends. So is language,” you tell Charlie in the novel, which is “not a problem to be solved or a device for solving problems.” Language, fictional you continues much like I assume you would in your essay had you been given to more poetic and less mathematical thinking, is “like a mirror,” but unlike you in the essay the literary Turing checks himself and says “no, billion mirrors in a cluster like a fly’s eye, reflecting, distorting and constructing our world at different focal lengths.” At another remarkable moment in the narrative when Adam speaks for the first time in public he considers that the “self” — sadly, a rare consideration among real people — might just be “an illusion, a by-product of our narrative tendencies.” Now, I know you had polemical reasons for speaking of solutions, especially in the context of a controversial topics like AI was when you wrote “Computing Machinery” in 1954, but I can’t help thinking, Mr. Turing, that mind of your linguistic prowess knows that language is not only a machine producing solutions or a technology producing resolutions. Language, in its historical and literary richness, can’t be reduced to the logic of a mathematical economy without sidelining the mysteries that are, counter to common sense reasoning, inhuman at least to the extent that they belong to the grammatical and rhetorical world of words not to the world of phenomenal things.

I’ve concluded nothing about AI or the Turing test, I know, though I need to conclude this letter, which I will do here with a reference to a dispute that took hold of a segment of the AI community in the decades following your death. A philosopher named Hubert Dreyfuss, prompted by the work of another philosopher, Heidegger, who like you gave language a pivotal role in human consciousness and thought, was vexed at the narrow triumphalism of the scientific community who righty felt on the verge of something big. In a series of books, he countered with the argument that AI is built on the analogy of engineering and managerial problem-solving techniques rather than on the philosophy of language. The problem, as he saw it, is that AI researchers and spokespeople assume that all understanding and all phenomenon can be rendered by a series of appropriate representations, a set of literal terms, precise propositions, empirical facts rather than beliefs, objective symbols not subjective procedures. It was, in short, yet another tendency to interpret reality as fundamentally absolute that goes back to the metaphysics of Plato and stretches to Cartesian rationalism. Here, everything that exists — an idea no less than an object — can be named and understood as a kind of empirical object, even though that idea or object can only exist in a historical situation or context. That element is the part of intelligence that is, for now, beyond simulation. It could be that the element beyond simulation is the often-cited multipurpose subjective notion of empathy or “emotional intelligence,” or the dubious unconscious, like the novelist Cormac McCarthy once said in an essay on AI, or it might be childish play as McEwan intimates or, alternatively, the fundamental despair at the very heart of all things as he also says with a reference to Virgil’s beautiful phrase sunt lacrimae rerum. Maybe it’s the disposition of a particular mind — at a particular moment on a particular Sunday evening — to call a cluster of words “beautiful” or to feel metaphorically moved by them, or the ability to be fascinated by language itself, much as the simulated entity in Mary Shelley’s seminal AI book, Frankenstein, who marvels at the “godlike science” of language. All of which is a too long way of saying, Mr. Turing, that you opened the possibility in your initial game and argument, that language is the decisive factor in consciousness and intelligence.