Dark clouds from the east snuffed the afternoon light. An urban train shrieked as it gained speed, and below, a swollen river meandered between a warped chessboard of dead and living trees on the valley’s slopes. Wind ruffled the city’s skirts, then suddenly began to toss debris into the air and hurl it against anything that was grounded. Shar was crossing the cemetery with her younger brother, Dex, when the wind started to blow memory pebbles off headstones into unmown grass. “Storm,” she yelled to Dex, who was checking out new graves with sunny curiosity. She gestured at the sky and together they ran down the slope, trying and failing to avoid stepping on graves. Bad luck from disrespecting the dead lit up their calves. They raced across a deserted road, down a circular drive, and through an iron door ripped off its top hinge into the foyer of an old self-storage facility.

Inside was quiet. Raindrops the size of Concord grapes exploded on the pavement outside, then it was as though gravity sucked water from the sky. Ten minutes later, the rain stopped. Shar and Dex listened. Shar was about to turn on her forever-last Callebaut flashlight when she felt Dex’s hand on her arm, his eyes wide. Something was hurtling toward them. She heard it take the corners of the storage unit rows at full speed. Dex grabbed his sister’s hand and they ran out of the building, round the back, and plunged into a scrubby, wooded area. Ten metres in, they hurled themselves to the ground and lay still. Low foliage and the dark clouds helped them disappear. The footsteps halted. Minutes passed. Shar turned her head toward Dex, who pressed his finger to his lips. Then, at last, the quiet pad of feet leaving. A hollow sound from deep inside the warehouse.

They stood and Dex led them deeper into the forest to a wall of thick ivy. He must have separated its darker density from the rest of trees while he was waiting for their pursuer to leave. He pulled off a vine and exposed a cement structure. Shar placed her hand on the cement and felt a subtle vibration. She stepped away. The ivy covered a cube about fourteen meters square and four meters high. They found the line of an entrance and tore more vines away, leaving a paisley pattern of furry beige roots on wood painted the colour of cement. There was no handle, only a lock. Dex took out a pocket set of Allen keys and a pocket set of picks and worked on the lock. Shar crouched against the wall and watched a little brown wren hopping silently in the underbrush. She enjoyed the slight rustle of leaves its movement made.

The lock clicked open and Dex pushed the door. Frigid air snaked over their faces. Inside, a single room, lit by dim blue light, contained twelve giant thermoses. The front of each thermos had a round window.

A white spark melts. Black void. Electrical current crackles. Black void. Fluid stretches small tubes. Sparks in red, blue, chartreuse, fuchsia. A soft whump. Whirring.

Out of the black fog of time unremembered, time without the possibility of remembrance, he throbs into focus, like the silhouette of a dark figure in a fedora and trench coat, a failing streetlight strobing behind him. He feels urgently like he should breathe, but breathing doesn’t seem to be in the realm of possibility. Impulses prickle and sparkle and crackle. He hears the movement of liquid, but cannot determine if the movement is inside him, or exterior, or both. Not a river, rain, or an ocean. More like pipes, a system of pipes.

Is he being born?

Yet surely a baby doesn’t know what pipes are, or the ocean, rain, or a river. Or a fedora for God’s sakes. Does a baby think, ‘for God’s sakes?’

He feels pain, but it doesn’t hurt. Where his neck is, there’s a searing sensation of edges, yet somehow that feeling is also neutral. Neither good nor bad.

Is he coming out of a coma? Has he been in an accident?

Death. Some accident.

Where did that thought come from?

A female voice enunciates from an echoless submarine and he tries to parse the sounds over a heartbeat too precise to be organic, shoom-shoom, “we circulate the perfusate,” shoom-shoom, “supplemented with all the micro-chemicals and micro-hormones the brain,” shoom- shoom, “needs, through the carotid via an oxygenating,” shoom-shoom, “pulse-generating pump. Upon exit, we run,” shoom-shoom, “the perfusate through the dialysis unit to remove waste products.”

A young male voice asks, “What about senses? Can it hear?”

It?

“Sight, hearing, smell, taste should be intact.”

“What about touch?” asks the young male.

“Anyone know what a ghost limb is?” the female voice in the echoless submarine whom he is identifying as some kind of teacher, asks.

He can hear now that many mouths are breathing. And smell the breath: candy, potatoes, pickles. He knows what a ghost limb is, but understands she’s not asking him.

“Serena?” says the professor.

He pictures a group of neurology students in an underground lab. Cream of the crop. Gathered round for the miracle of his rebirth.

Rebirth?

“It’s when a person still feels pain, or an itch in their leg or arm, even after it’s been amputated? Like they can never scratch it ’cause it isn’t there?”

He’s puzzled that an elite neurology intern would use the diction of an uncertain teenager. His wife, who loathed this type of speech, would say, “They’re not asking a question, and they’re not uncertain. Trust me.”

“We will test to see if he feels ghost limbs.”

A bit rudimentary for advanced neurological research, he thinks.

“Whoa, so not chill,” says a male voice. “An itch you can’t scratch.” The group laughs.

“Chill?” says another student. They laugh again.

His eyes pop open at last.

Serena exclaims, “Look, his eyes are open!” He has a blurry sense of all their eyes swiveling in his direction.

He wishes he could wipe his eyes but, like breathing, that doesn’t seem to be in the realm of possibility. He blinks rapidly. A group of teenagers come into focus. They hold up their phones, which have an industrial and indestructible design, and take selfies with him in the background. He tries to make out what he looks like on their screens, but he can’t see at that distance.

They check each other’s photos and discuss possible taglines. A memory floats up. His wife, looking way up into a forest canopy, listening to chimpanzees he couldn’t see calling to each other. The psychic charge in the air from the chimpanzees’ connection to each other had made his face tingle. He feels it now, between these students. A sound expels from him, a short coo, which the voice synthesizer makes sound like the toot of a boat horn. Everyone looks at him. His wife had wanted to see the apes in the ‘wild,’ before they existed only as creatures in a zoo.

A middle-aged woman, presumably the teacher, comes around to take a selfie too, and because she is close, he catches the vision of himself on her screen. He gasps, which the synthesizer translates as a pneumatic sound.

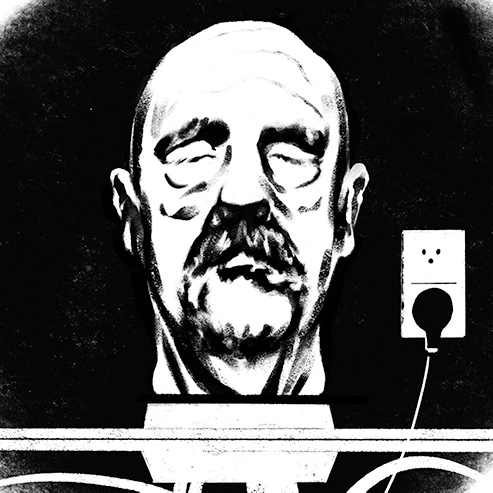

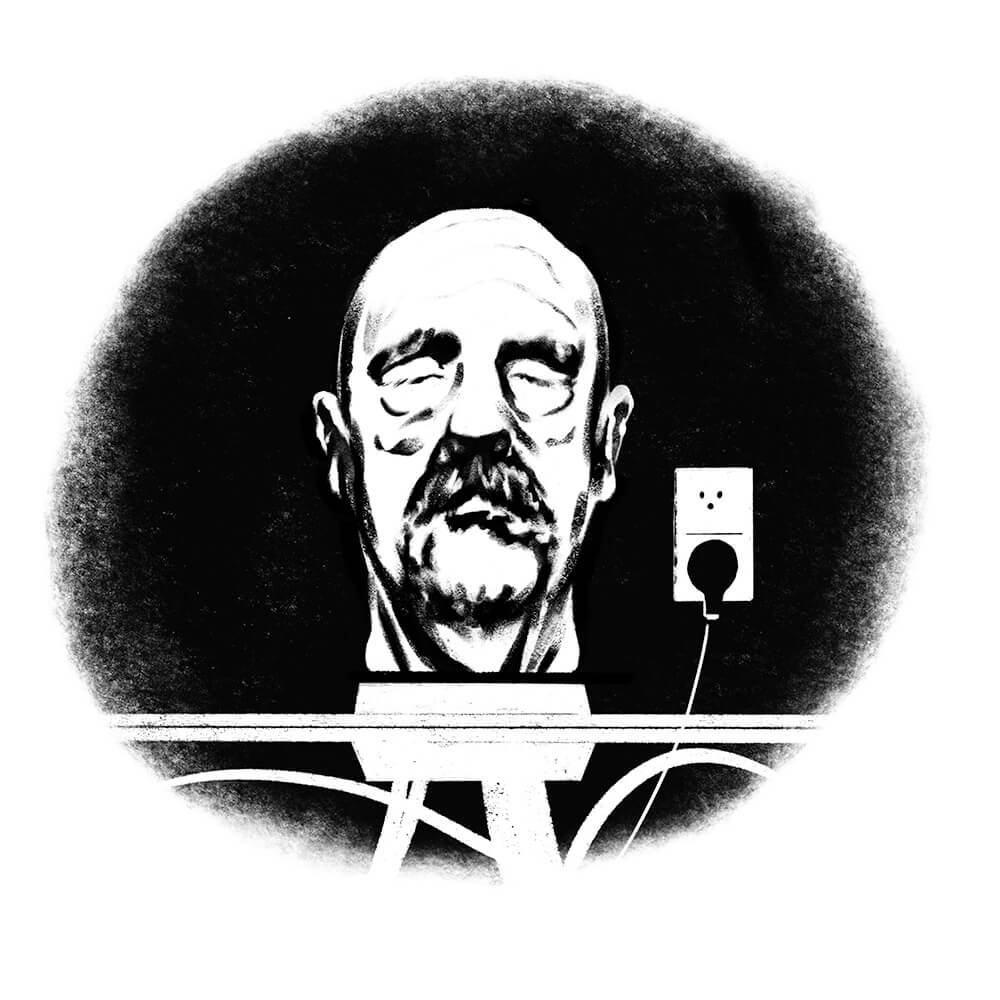

Below his head is a transparent box with tubes and wires and a pump and what looks like a backup generator (for which he is grateful) and a long black cord plugged into an electrical socket.

He hears his wife’s voice, “I don’t want to wake up with everyone I love dead.” His remembered answer, “I’ll be there.”

She, “we have to make room for the generations to come.”

He, in a rage, “You’re okay with just disappearing? Everything we have worked for, learned, become? Aren’t you at least curious?”

“No. I’m satisfied. You are spending our children’s inheritance. You are squatting on their future.”

He shuts off memory. A horrible vulnerability assaults him. He can’t see anything behind himself. He experiences a powerful flight or fight reaction, with neither action available.

“Make sure nobody trips over that plug,” he orders, his terror extreme, but also weirdly cool since no endocrine system drives it.

A throaty chuckle. “He’s a cute one, isn’t he? Telling, not asking.”

His blood freezes. Or whatever it is that runs through his veins. He needs to be on her good side.

“Sorry. Habit. I used to be the boss of a lot of people. We made the best cartoons of all time. You know Mickey Mouse? Minnie Mouse? Goofy?”

The students look blank.

Mickey didn’t make it to the future? He’s rattled. That was going to be his magic card.

“I’m Walt Disney. I created a new industry. I shaped American culture. I made stories people yearned for — wholesome, optimistic entertainment — and, by the way, I made a lot of money in the process.”

The students’ eyes narrow. Clearly not a popular feat.

“Ms. Ronan? Can we start the experiments now?” asks a young lad with the build of a heavyweight boxer.

“Experiments?!” The voice synthesizer translates his intonation perfectly.

Some of the students laugh at the expression on his face, a classic cartoon double-take.

Ms. Ronan, who can’t see his face, answers, “We will establish a baseline for identity retention. Who our subject thinks he is. We can control the volume of flow of the perfusate to different parts of the brain. We will determine which part of the brain does what by reducing the flow and recording changes.”

The head asks, “But if you reduce the flow of… perfusate… won’t that risk damaging parts of my brain?”

An awkward silence ensues.

“What year is this?”

“2047.”

“Does the president know I’m alive? The military? The surgeon general? Can I make a phone call? My existence is a miracle!”

“No offense,” says Ms. Ronan, “but apparently you all say something like that. If my kids hadn’t found you behind an abandoned warehouse — your backup power was almost depleted, you had been cut off the main power grid — if they hadn’t found you, you would have been in a pickle. Well, pickled.”

“All?” the head asks. Even without an endocrine system, anxiety sirens are screeching in every part of his brain.

“There’ve been tens of thousands of you. Mostly older white men who had the means. Convinced the future would want you.”

“But I’ve got a contract. Viva ’N’ Finity Vitality Extension Products, based in Monterey, California. A trust in perpetuity. Call them.”

“He’s telling not asking again Ms. Ronan.”

“Walt. Seriously? You know perpetuity doesn’t really exist don’t you?”

“Call my daughters. They’ll pay.”

Ms. Ronan’s tone grew gentle. “Do the math Walt. We’re likely talking about your grandchildren or great-grandchildren. Society has been restructured. There are no mega-wealthy people anymore.”

“My company then. The Disney Company. I’d be a huge asset.”

One of the students raises his mobile and voices, “Contact Disney Company, human resources.” He puts it on speaker mode. “You have reached the Walt Disney Company personnel office. Please press one…”

“I hate phone trees,” the student says.

“No, don’t hang up,” says Walt.

“He’s doing it again,” comments the student and presses a button.

“How may I direct your call?” says the receptionist.

“I’ve got one of your former heads,” the student chuckles, “you know from Viva ‘N Finity Vitality Extension Products? Anyhow, he says he’s Walt Disney and that you’ll pay us lots of money for him.”

“We haven’t had one of those in months. One of Viva’s technicians from the 2020s programmed a brain worm into clients’ minds just before freezing that made them think they were Walt Disney. Walt Disney was cremated in 1966. His ashes reside in First Lawn Memorial Cemetery.”

“Oh God,” the head croaks. “Who am I then?” The students look at him with dawning compassion.

“Class,” Ms. Ronan intervenes, “I am going to pull the plug on our experiments for today.”

“But that’s murder,” the head says.

“Just a turn of phrase, Walt, or whoever you are. Though I should say, technically, you are not alive. NASA defines life —class, make a note of this, it will be in the exam — as ‘the ability to take in energy from the environment and transform it for growth or reproduction.’”

A girl at the back of the class raises her hand. “Ms. Ronan. Can I be excused? I’m really not comfortable with this. Maybe it’s not murder, but it feels cruel.” Other heads nod in agreement.

Ms. Ronan VRs the deluge of parental complaints. “No need, Melanie,” she says. “One of my sisters is a neurology professor at an ivy league university. I’m going to transfer ‘Walt’ over to her. She’ll know what to do.”

Our parents were jokesters in a serious time, from Quebec, the north-eastern part of Canada, before colonial boundaries were dissolved. They named my older sister Roxy, me Foxy, and my younger sister Moxy. My sisters go by their first names, but I go by my last name, Ronan. Lately the fashion in baby names is organic and gender neutral — Iron, Oxygen, Lichen, Water, Copper — or species near extinction — Orca, Murrelet, Tiger, Chimp, Gorilla, Oriole. My sexual partners are the only ones I allow to call me by my first name. They do so unironically, I assume. I could use the past tense because in truth it’s been five years, no, six, no seven since my last sexual congress.

I live in Canton 45, formerly known as Boston. I’m a professor of clinical neuropsychology. We are relics. The university must focus on the nuts and bolts of human life, the basic, mechanical issues of survival. Engineering and geophysics get the dough. Still I would argue (not that anyone would bother to disagree) that identity and memory are also matters of survival for humans.

My office is in an old building on the edge of campus. Not one of those grand old brick building covered with ivy, but a squat, concrete structure from the 1970s with oblong windows. Modernist. A label that exudes narcissism or doom, for what can come after? They squeezed in post-modern, a last nail in the coffin, along with Generation Z.

Perhaps narcissism is harsh. Maybe it’s careless indifference, or a lack of ingenuity.

I have a room on the ground floor at the back corner. My window overlooks the scraggly evergreen shrubs that have been planted around the building’s base — dead twigs and branches darkened by rain with a few nipples of new green needles on some twigs. The intercom announces the arrival of the delivery I’m expecting.

I open my office door and listen to the wheels of a delivery trolley, the hum of a generator, the whir of an engine, the whump-whump of a pump. The trolley rounds the corner and I see a large covered box. The delivery woman meets my eye and shouts over the drone of the generator, “Are you sure you want to receive this?” and I wonder if she suspects the package is illegal and plans to report me.

“It’s for research,” I nod. “I will call for disposal when I’m done.”

They help me lift the box onto the table and wheel the generator in place. They leave.

I remove the cover. He looks like a three-dimensional death mask. His eyes are closed, his skin looks as bloodless as it is. His head is shaved except for a fringe of straggly black hair at the base of his skull that would have been shoulder length if he had had shoulders. I can’t imagine this hair style could ever have been thought attractive. The hair looks dyed. He has a full salt-and-pepper moustache joined to two lines of white beard that follow his laugh lines down to the end of his chin. His age is hard to determine but the whiteness of his beard and the lines on his skin suggest a man somewhere in his seventies. This is my first talking head.

I remove the plexiglass case. I plug his machines into the office power source, check twice to make sure I haven’t missed anything, and disconnect him from the generator. When I turn it off, quiet pillows the room. Nothing but the soft whirr of the perfusate pump, the small motor for the pulse generator, and crows calling each other out over a scrap of garbage. I remove the clear, protective box, cover his scalp with conducting gel, and gently place the sensor helmet on. Two screens light up. One shows several neon-coloured islands with lighter outlines, like beaches in an aerial view of an island, and one shows white lines of connectivity, webs or nebulae like many-legged baby spiders. I push the connector on the helmet in more firmly and a third screen lights up with horizontal images of brain waves.

I replace the perfusate infused with Moxy’s cortical blocker with a clean perfusate. His eyes pop open and my screens light up with activity.

“You’re the sister,” he says in his ersatz voice.

“Yes. Ronan. Pleased to meet you.”

He looks around the room. “No students?”

“Maybe a couple, later.”

An anguished expression seizes his features. “I don’t know who I am.”

“Moxy mentioned calling you Walt?”

“Anything but that. I curse the cruelty of whoever introduced that brain worm.”

“I believe the panel on your thermal unit read, Oscar, Oscar Larue.”

“A name, yes, but not a self.”

“Perhaps my questions will help. Do you know why you got yourself preserved?”

“I…” He hesitates.

I look at him and say, “I’m paying complete attention to you even though I’m looking at the screen because I must simultaneously read the transcription of our conversation to make sure there are no errors. Sorry.”

He looks up at the ceiling as a way of turning his mind inward. “I was dying. I knew I was dying. I had nothing left to lose. Who wouldn’t want to live longer if they could?”

I look up from the screen. He has closed his eyes. “And now Mr. Larue? Are you happy with your choice?”

He opens his eyes and looks at me for a long time. His gaze feels fundamentally different from the way anyone looks at other people now. He doesn’t know who he is, yet his sense of self hits me like a hot wind. For the rest of us who aged normally, the Age of Individualism (the Age of I) began to ebb forty years ago. Because it ended not through a change in ideology, but rather as the natural result of historical forces, its finish was not associated with violence, besides a spasm or two between 2015 and 2020. No man is an island is now an utterly banal statement.

“I didn’t anticipate what it would be like not having a body. Believe it or not, in my desperation to survive, I didn’t think about it.”

I scan the transcription. “And what it that like? Not having a body?”

“I must rely only on speech and my ears and eyes to survive. I can only see what’s in front of me. I cannot run away. I cannot hide. I am utterly exposed and dependent.”

“You can hide your thoughts.”

“Can I?” He concentrates on a thought and checks to see if I can read it.

“I assume,” he asks, “I have no money left?”

“Even if you did, the system doesn’t work that way anymore. Surplus only buys you small privileges, which you share with your family and friends. It would not help your chances of survival.”

Oscar closes his eyes again. A conflict between terror and curiosity appears to be taking place inside him.

“Do you have anything to help with anxiety? Can you add something to the perfusate? I feel like I am suffocating.”

I start to explain that he doesn’t need to breathe. He interrupts me. “I know I am not suffocating. I feel as though I am suffocating.”

I write, Subject retains automatic memory of breathing. How long for unconscious biological pathway to rewire?

“Do you remember when you first regained consciousness?”

“Yes. Everything.”

“How do you know your memories are accurate?”

“Are you trying to torture me?”

“Mr. Larue. I am a clinical neurologist. I am interested in the intentional component of memory. In particular, its function in creating and maintaining identity.”

“And I am desperate to know if you will let me live.”

Now it’s my turn to stare at the ceiling. I’m intrigued by how much of a person he is. I thought this would be a simple exercise of getting the information I needed for my research and unplugging him. I don’t want to keep him forever certainly, and the government has its hands full keeping people who are genuinely alive, alive. Keeping him would be worse than having a child, because he would never grow up. It would be worse than having a pet, because he won’t die naturally. I would have to keep him for the rest of my life. Why would I take on such a burden when the result, sooner or later, is inevitable? Yet is it ethical to lie to him? Would I want to know my fate if I was in his circumstance?

“Mr. Larue, those terms don’t apply to this situation. You are not alive.”

“But I exist.”

“So does a stone.”

“I have consciousness.”

I look again at the ceiling and notice a stain, a brown outline shaped like a cloud.

“It is murder,” he says, “in the eyes of God.”

“We don’t think about God anymore.”

“A figure of speech. Is anything sacred?”

“Yes, life is sacred. All life is sacred.”

“Then….”

“You have already lived Mr. Larue. Your continued existence would mean someone else cannot live. There are not limitless resources.”

His eyes go glassy. A tear gathers in the corner of one eye, then rolls down his face and hits the floor.

“‘And all our yesterdays have lighted fools the way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle.’”

I note the intentional memory of Shakespeare with appreciation.

“It dawned on my wife and I that there would be no final arbitrator for our arguments, which were passionate and many, but we argued as if there were. We realized we would never know which of us was finally right about everything, there would be no judge at the pearly gates, and we laughed together at the absurdity of the fact that we acted as if there was.”

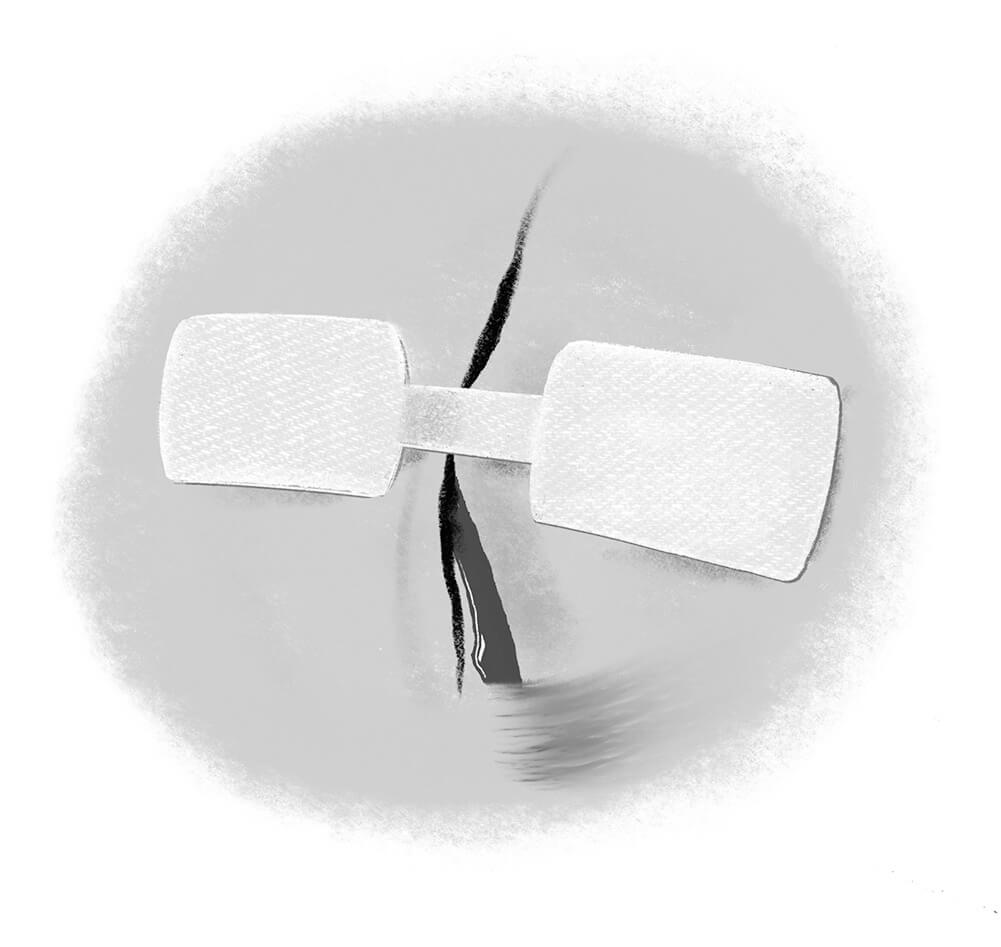

He begins to laugh, and the large movement of his features causes a small fissure to break open in his forehead. Perfusate leaks out and runs alongside the bridge of his nose. I am frightened as he keeps laughing. Will I be able to sew the fissure? What will happen to his skin if I do?

He notices my alarm and says, “She was right, about everything.”

“Your skin has opened on your forehead. I am going to put a butterfly bandage on it and hope that it stops leaking.” I get my first aid kit from the cupboard and wheel my chair over to him. I cut a bandage, stick one side on his forehead and gently pull the skin together before sticking on the other leg. I prepare another bandage.

“I only wish I could tell her. She would have taken a small, ironic satisfaction from it and we would have made amazing love afterwards.” He gives a rueful smile. “You can pull the plug anytime.”

I don’t know where the impulse to kiss him comes from, but the words Kiss me quick for soon we’ll die cross my mind.

“Can I kiss you?” I ask.

He looks sad. “I’d rather you didn’t. I still have the physical memory of kissing her and I don’t want to risk losing that.”

I return to my computer and write, “Human memory may not be primarily about identity or learning or survival. Its primary purpose may be the brief airy preservation of connection between us.”

“Are you thinking about that kiss?”

I continue to type. “And that preservation may feel eternal because it is sealed in a single consciousness which will never know itself not to exist.”

“Yes,” he answers and closes his eyes. I walk over and infuse the perfusate with the cortical blocker. I could not bear to continue this research.

Weeks later, Shar and Dex went foraging for adventure again after dinner. They played tag in the cemetery and the bad luck they’d channeled running over the graves earlier was replaced by a feeling of joy. How would the dead not have been happy to have children playing near their graves, Shar thought. At dusk they wandered down the hill and, avoiding the storage facility, made their way into the forest and the hidden building.

Dex had no problem picking the lock again. The door swung inward. They switched on their flashlights and stepped inside. The thermal units had been removed, but the frames and name plaques remained. Shar went around and shut the gates, looping the wires behind neatly over the crossbars.

“Let’s go to the pond next and look for tadpoles,” Dex said. He closed the door behind them and they heard the latch of the lock click into place. Shar felt as though they were closing the covers of a book with a story they knew, but had not actually read.

Graphics/Design: Adam Meuse